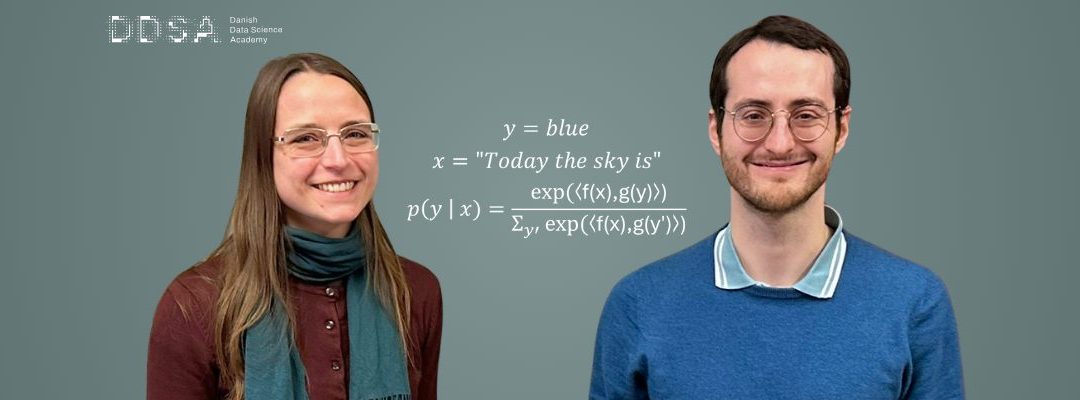

Together with Emanuele Marconato and Andrea Dittadi, the young Data Scientists, Beatrix M. G. Nielsen (to the left) and Luigi Gresele, have written a strong scientific paper about the deep inside of deep learning machines.

Frustration.

That feeling marked the beginning of an idea that has since evolved into a research paper to be presented next week at the EurIPS conference in Copenhagen by Beatrix Miranda Ginn Nielsen and Luigi Gresele – two of the most interesting and talented emerging voices in data science in Denmark.

Luigi is a postdoctoral fellow at the Copenhagen Causality Lab at the University of Copenhagen, and as of 1 December, Beatrix has joined the IT University of Copenhagen as a postdoc. Both have been, or are currently, funded by the Danish Data Science Academy.

The paper, “When Does Closeness in Distribution Imply Representational Similarity? An Identifiability Perspective,” co-authored with Emanuele Marconato and Andrea Dittadi, will also be presented almost simultaneously at the NeurIPS conference in San Diego, USA.

Focusing on machine learning and artificial intelligence, the paper looks at what goes on inside two different versions of the same deep learning model – for example, two large language models – when they are given the same input.

But now back to the initial frustration.

“I was frustrated with the lack of understanding of how models work,” Beatrix recalls. “I enjoy puzzles and creative thinking, and I wanted to figure out whether we can understand these models better by abstracting away the details.”

She and the team, however, could not simply ask model developers how these systems work internally. As Beatrix notes:

“They don’t understand it either.”

Luigi elaborates:

“We know how to plant the seed of an algorithm. The algorithm learns from data and modifies itself. But at the end of the process, we don’t truly know how it works internally. It’s like when a child learns something: we don’t really know what’s happening inside the child’s brain.”

The four researchers set out to investigate the inner workings of these models: this became a central theme in their work, which took them 18 months to complete.

Luigi explains:

“Two different models can achieve equally good performance while being internally different. Because it is a fact that there are different ways in which a model can implement an equally good solution – something one can establish through an identifiability analysis, which was the starting point of our work.”

A key question in their work is whether deep learning models that perform almost equally well also end up being internally similar. More formally, it asks how closeness in the distributions generated by the models relates to similarity in their internal representations.

“Your research demonstrates a way to measure representational similarity between models. In which cases is having similar representations across models an advantage?”

Beatrix responds:

“This is, of course, always a discussion: do we want our models to solve problems in similar ways or in different ways? An example where you might not want models to give similar answers, would be if you actually want to figure out if there are different equally good ways of solving a problem. I mean, if you have a problem where the question of interest is in which different ways could you solve this problem well? Then, there you would like to train a number of different models with different representations and see whether you could get several models with different representations which get equally good performance. Tunnel vision is not preferable, so we need to look into this aspect more in the future.”

The next step is the poster presentation at EurIPS on Thursday, 4 December. Beatrix and Luigi hope for broad engagement. Beatrix says:

“Conferences are exactly where you receive valuable feedback, and we already see strong interest from the community. I hope that after EurIPS and NeurIPS more people will focus on understanding models. This type of research is genuinely missing.”

Their work, however, does not end at EurIPS or NeurIPS. Their next study is already underway. Luigi explains:

“Our follow-up project extends our NeurIPS/EurIPS paper to study knowledge distillation, a method for training a smaller ‘student’ model – small enough to run on a laptop or phone – to imitate a much larger ‘teacher’ model that requires a huge data center. We investigate whether the student can not only achieve the same results as the teacher but also arrive at those results in a similar way – in other words, whether the student learns representations similar to the teacher’s.”

Given your expertise, is it tempting to engage more directly in the public debate about deep learning?

Luigi reflects:

“I find many of the current explanations of deep learning models very problematic. The difficulty is that I don’t yet have a better alternative. I hope our work contributes to a deeper understanding and stimulates more informed discussions. If we have added even a small step toward a clearer picture, I am satisfied.”

Beatrix adds:

“I also find the lack of model understanding troubling. Our research is not aimed at improving model performance, but we do hope our findings contribute to the next generation of deep learning models.”

The Paper and the Upcoming Follow-Up

The paper “When Does Closeness in Distribution Imply Representational Similarity? An Identifiability Perspective” is authored by data scientists Beatrix M. G. Nielsen, Emanuele Marconato, Andrea Dittadi, and Luigi Gresele. It will be presented almost simultaneously during the first week of December at the EurIPS conference in Copenhagen and the NeurIPS conference in San Diego, USA.

The abstract of the paper is as follows:

‘When and why representations learned by different deep neural networks are similar is an active research topic. We choose to address these questions from the perspective of identifiability theory, which suggests that a measure of representational similarity should be invariant to transformations that leave the model distribution unchanged.

Focusing on a model family which includes several popular pre-training approaches, e.g., autoregressive language models, we explore when models which generate distributions that are close have similar representations. We prove that a small Kullback–Leibler divergence between the model distributions does not guarantee that the corresponding representations are similar.

This has the important corollary that models with near-maximum data likelihood can still learn dissimilar representations – a phenomenon mirrored in our experiments with models trained on CIFAR-10. We then define a distributional distance for which closeness implies representational similarity, and in synthetic experiments, we find that wider networks learn distributions which are closer with respect to our distance and have more similar representations. Our results thus clarify the link between closeness in distribution and representational similarity.’

Now, the data scientists will follow up their work. A quick description is:

‘The follow up work extends our NeurIPS/EurIPS paper to study knowledge distillation, which is a way to train a smaller “student” model, that is small enough to run on your laptop or phone, to imitate a larger “teacher” model, which needs a huge data center to function.

Our work investigates whether we can make the student not only get the same result as the teacher, but arrive at the result in a similar way, i.e. whether the student model learns representations which are similar to those of the teacher.’